An interesting feature of the Geditsias is that the same individual may have pinnate and bipinnate leaves or, as can be seen in this photograph, exceptionnally have partially pinnate and bipinnate leves. This leaf belongs to Gleditsia sinensis (Royal Botanic Gardens of Madrid).

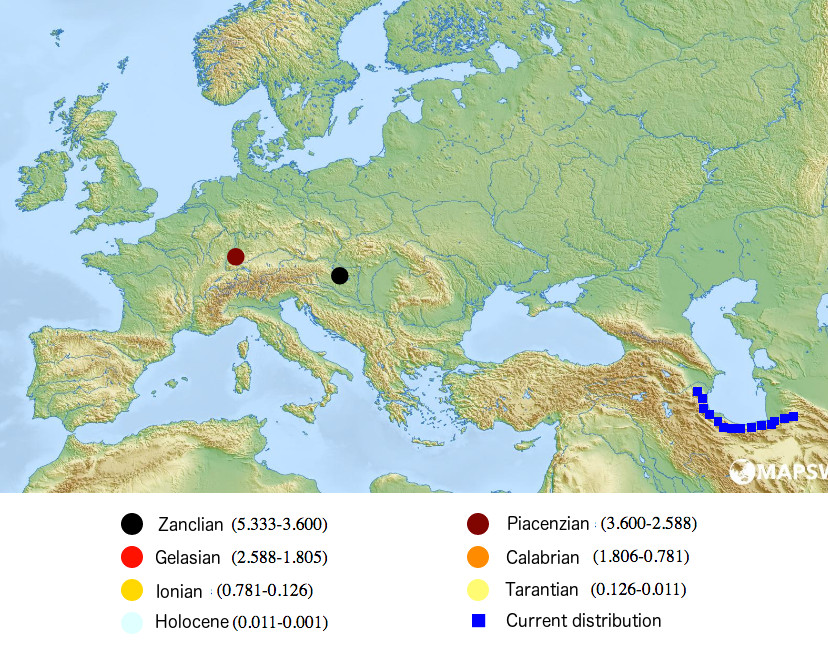

The genus Gleditsia, composed of about 14 species, is another clear example of taxon with disjunct distribution area, with 3 species present in the Americas and all the others in Asia. One of these species is present in the southern Caspian Sea and this allows us to intuit that this genus was probably present throughout the Northern Hemisphere before the glaciations. As shown in the map below, there is little fossil evidence of this kind in the Pliocene or in the European Pleistocene, and these are not sufficient to know its spatial and temporal distribution. But it confirms, however, that the genus had a holarchic distribution before the ice ages. The return of this genus to the European continent, curiously, was not made from its stronghold in the basin of the Caspian Sea, but of the American continent. The honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos), originally from a large area of North America, it is now naturalized in much of the European continent. It is even even cultivated in the area where the Gleditsia caspica originates and it is verified that both species hybridize very easily. A recent study (1) conducted in Azerbaijan has shown that even in nature reserves many of the observed individuals are already first-generation hybrids. This example shows that despite the long time that both species have separated, the speciation process has not yet succeeded in preventing or hindering the crossing of the different strains of this genus.

The honey locust is an interesting case of an orphan species. Provided with dissuasive spines on a large part of its trunk and its branches, it produces fruits with a sugar pulp highly appreciated by herbivores, it is very interesting to note that there is currently no herbivore species that preferentially feeds on its fruits or leaves and which actually co-evolved with this species. In North America, it is suspected that they are probably elements of the recently disappeared megafauna, such as giant sloths, which ate their fruits and contributed to spread the seeds (2). In Europe, it is not so clear what kind of herbivore it would interact with, although observations in Argentina suggest that other large herbivores could also have fed on their vegetables. Livestock in this region are the main contributors to the spread of this species.

Male flower of Gleditsia sinensis (Royal Botanic Garden of Madrid). The flowers are actinomorphic. Petals and sepals are very similar to each other.

| Gleditsia | Familia: Fabaceae | Orden: Fabales | |

Trees or shrubs, deciduous. Trunk and branches usually with stout, simple or branched spines. Leaves alternate, often clustered, simply paripinnate and bipinnate often on same plant; stipules caducous, small; rachis of leaves and pinnae sulcate; leaflets numerous, subopposite or alternate, base oblique or subsymmetrical, margin serrulate or crenate, rarely entire. Inflorescences axillary, rarely terminal, spikes or racemes, rarely panicles. Flowers polygamous or plants dioecious, light green or greenish white. Receptacle campanulate, outside pubescent. Calyx 3-5-lobed; lobes subequal. Petals 3-5, slightly unequal, ca. as long as or slightly longer than calyx lobes. Stamens 6-10, exserted, slightly flat, broad, with crisped hairs from middle downward; anthers dorsifixed. Ovary sessile or shortly stalked; ovules 1 to numerous; style short; stigma terminal. Legume ovoid or elliptic, flat or subterete. Description: Flora of China | |||

Legumes of Gleditsia triacanthos in the Park of Retiro (Madrid).

Species cultivated in our parks for a long time and from which also developed a variety without thorns. It seems, however, that its classification as an invasive species condemns for now this species to stop being used as an ornamental tree. Its wide naturalization, however, guarantees for the moment its survival in our flora.

| (1) Schnabel1 A. & Krutovskii K. (2004) / Conservation genetics and evolutionary history of Gleditsia caspica: Inferences from allozyme diversity in populations from Azerbaijan / Conservation Genetics, Vol.5, pp. 195–204, 2004 | ||

| (2) Whit Bronaugh (2010) / The Trees That Miss The Mammoths / American Forests (Winter 2010 issue) | ||

Author: Adrián Rodríguez

Translation: João Ferro